Co-written by Sarah Herron and Morgan Tilton

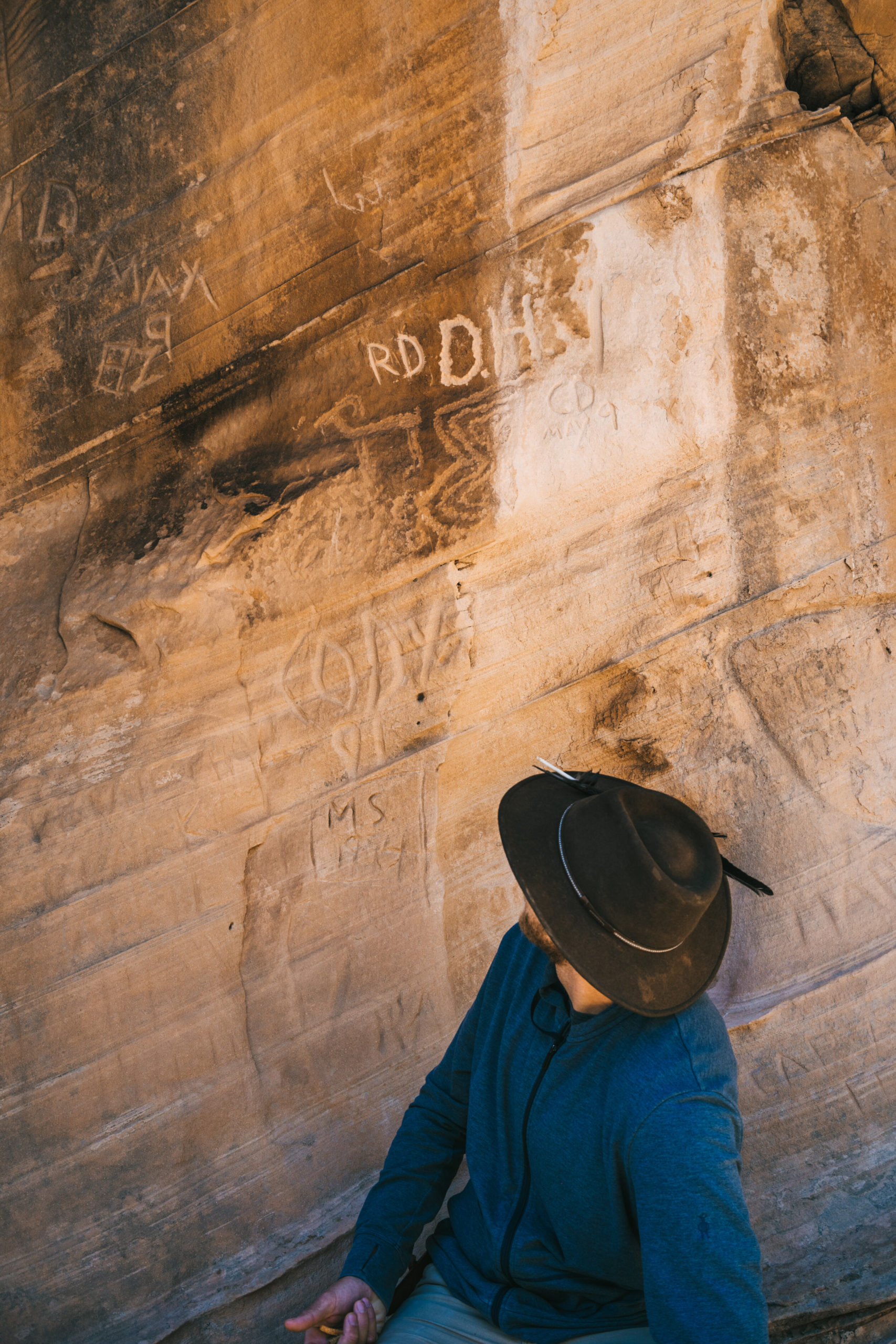

Photos by Dylan H. Brown

I had never backpacked when I met my life partner Dylan, three years ago. At the time, I was an Angeleno and nine-to-fiver. I didn’t have a stereotypical outdoor lifestyle or fit the adventurous, dirty-boots archetype. I definitely didn’t know any Leave No Trace principles—or that they existed.

Dylan, on the other hand, was a lifelong mountain, desert, and river explorer with vast understanding of outdoor ethics. And that’s OK: We are ALL beginners at some point in time, including all of the greatest teachers and guides.

According to The Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics, “90% of all people in the outdoors are uninformed about their impacts.” LET’S CHANGE THAT (we’re totally capable). Regardless of your experience level, it’s laudable to seek more education and to aim for improved practices. We can all cultivate a deeper integrity for our impacts in the wilderness, whether that’s our backyard or across the world.

Here are the most important foundational outdoor ethics that everyone from newcomers to veterans should know.

Leave No Trace: Outdoor Principles You Should Know

When I lived in Los Angeles, my go-to outdoor space was a county park near my apartment and the beach. Leave No Trace (LNT) principals apply there, too! Today, my access looks a lot different. There are generally fewer crowds scattered across the patchwork of National Forest and federal land in my backyard.

Back in the ‘70s, the first-ever “no trace” guidelines were created for wilderness-goers, backcountry travelers, and campers. LNT rules are not static and they’ve evolved over the decades. But, the core of these ethics reaches across time and culture. And they’re applicable to every natural space we know today—which is so cool!

With a conscious approach and simple checklist, we can all return to the places we love and find them just as pristine as the first time we went.

*The list below is my own adaptation of the official “Seven Principles of Leave No Trace” framework. Read the full LNT guide here.

Leave What You Find

On social media and up-and-down trails, it’s very easy to see evidence of humans in nature. The goal, though, is to NOT be an overt traveler. Picking wildflowers, carving or hammering into trees, taking home petrified wood and colored rocks, or disturbing cultural artifacts are all big no-nos. The lattermost acts are even illegal on public land!

Pack it in, Pack it out

I love this mantra! It’s so simple and easy to remember. Before walking away from your campsite, rest area, or lunch spot, take an extra minute to look around. Pick up any trash—like those annoyingly tiny pieces of plastic from snack food wrappers. Pack out any leftovers: yes, even crumbs, fruit peels, nut shells, and bacon grease.

Now—everyone take a deep breath—because we need to talk about human waste. (We ALL need to go at some point!) Tampons need to be packed out rather than buried or burned. The same goes for toilet paper—at least, that’s the easiest option. Both can be packed out in a plastic bag. For number two, you typically dig a hole with a trowel. AWAY FROM WATER. Make sure you’re at least 200 feet away from any water source, trails, and camp. Dig a hole about 8 inches deep. Do your business. Afterward, the hole should be covered with soil and inconspicuous.

There are also sensitive backcountry locations, like narrow canyons or fragile alpine landscapes, where holes won’t work. Instead, solid human waste needs to be carried out (it’s not my favorite activity). For those trips, we use wag bags. If you only need to go number one, things are more complicated. Generally, go pee 200 feet away from a water source. Except, if you’re on a river trip (kayaking, standup paddleboarding, whitewater rafting, etc.) Then, you typically go in the water, according to American Whitewater. (I know, I know. It’s contradictory! But that’s the rule of thumb.)

Don’t Build Cairns

A cairn is a human-created pile of stones that’s typically used to mark a route. You’ve probably seen these structures on your own hikes. Many photos on social media glorify these rock towers. The first few times I saw cairns, I enjoyed their purpose and symbolism. They directed me. And I felt comforted by their voyage support, like a compass or the North Star to guide the way.

But then I saw a FIELD of cairns on a hike and was shocked. A dozen or more cairns—some taller than me—completely disrupted the landscape and view not to mention wildlife habitat. Cairns can serve a significant purpose along a trail for navigation but should not be for self-indulgence. The literal movement of rocks is also against LNT principal #4 and #7: Leave What You Find, and Be Considerate of Other Visitors. (If you’d like to read more about cairns, I really appreciate this Bearfoot Theory blog post, written by Kristen Bor.)

Photo by Claudio Schwarz

Tread Lightly

To avoid harming the environment, it’s imperative for us to follow a trail that’s already been created. It’s NOT good to create a new path. But, if a designated trail doesn’t exist, it’s vital to pay attention to the surface and vegetation where you walk. Rock, sand, and gravel are the most durable against foot travel. Dry grasses are more durable than wet meadows. There, everyone in the group should spread out.

And a very extraordinary type of soil should be completely avoided, because it’s actually alive: cryptobiotic crust. This texturized desert soil is home to minuscule organisms with a dark tint—so keep your eyes open for those areas! It’s a beautiful sight. Avoid stepping on this earth by using rocks and follow in each other’s footsteps.

Also, I never would think that desert mud holes are a no-step zone—but critters can live there! So, avoid splashing or stomping in those puddles.

Geotagging: Be Broad, Don’t Use

Geotagging is a tool on social media that marks the location where your shared photo was taken. Every person deserves to experience the world’s beautiful wonders, and withholding information is a form of gatekeeping and classism. Guidebooks, maps, and online forums are excellent open-source tools where information is shared. However, geotags also easily streamline hoards of people—who have not all researched that location’s environmental sensitivity—to that spot. The latter can also lead to incredibly frightening, unsafe situations!

In middle-of-nowhere Utah backcountry, Dylan and I once drove by a stranded young couple, from Denver, in a front-wheeled rental. Their car was stuck in a sandbank, and it was a late winter afternoon. They had no water. No warm layers. No food. No sleeping bags. They were more than 40 miles from the main road. And they would have spent the night in sub-freezing conditions. They were heading to the Cosmic Ashtray, a unique geologic formation that they learned about via an Instagram geotag.

Even LNT recently established social media guidelines that include geotagging, because it’s urgent for travelers to consider the potential impact of how they share location info. If you geotag a location, choose a broader area, such as a National Park name or nearby town. Those who are prepared and eager to find your precise location can responsibly research and educate themselves on the area. A sense of discovery and self-reliance is (and always has been) meaningful for anyone who ventures into the wilderness. And, if you do geotag, dovetail that location-share with education on how to protect and care for that place.⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

Don’t Feed Animals

Wild animals are adorable, fascinating and we all want a picture with them. I get it! But it’s incredibly sad to think that feeding one could cause them stress or permanent harm—it’s not worth the impact. If a young animal is lured or removed from their parents, they might be abandoned. It’s best to observe wildlife (and discretely, quietly take photos) from afar.

Ultimately, we all want our most memorable, special outdoor places to remain just so. Regardless of our experience levels or where we live in the world, we can all strive to be better stewards of our backyard playgrounds.

Comments +